Thématique 1

Enseignement d’une Matière par l’Intégration d’une Langue Étrangère (EMILE ; CLIL– Content and Language Integrated Learning en anglais)

Enseignement d’une Matière par l’Intégration d’une Langue Étrangère (EMILE ; CLIL– Content and Language Integrated Learning en anglais)

Voir les conférences

Thématique 2

Apprentissage et enseignement des langues autochtones, secondes et étrangères dans un contexte plurilingue.

Apprentissage et enseignement des langues autochtones, secondes et étrangères dans un contexte plurilingue.

Voir les conférences

Thématique 3

Contextualisations didactiques, approches théoriques et pratiques.

Contextualisations didactiques, approches théoriques et pratiques.

Voir les conférences

Thématique 4

Pédagogies innovantes et nouvelles technologies dans l'enseignement.

Pédagogies innovantes et nouvelles technologies dans l'enseignement.

Voir les conférences

Thématique 5

Pratiques effectives et pratiques déclarées, transmissions à l’école et en famille.

Pratiques effectives et pratiques déclarées, transmissions à l’école et en famille.

Voir les conférences

Filtrer les conférences

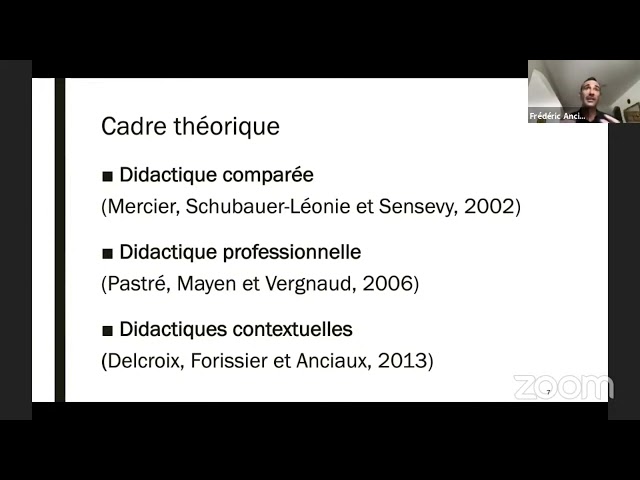

Cette présentation vise à analyser la notion de contextualisation dans l’enseignement en fonction de différentes disciplines scolaires au collège. À travers une analyse des programmes scolaires nationaux et des discours d’enseignants en Guadeloupe, l’objectif est d’identifier des types de contextualisation et des gestes professionnels, spécifiques et communs, selon les matières enseignées en vue de dresser des profils disciplinaires de contextualisation didactique.

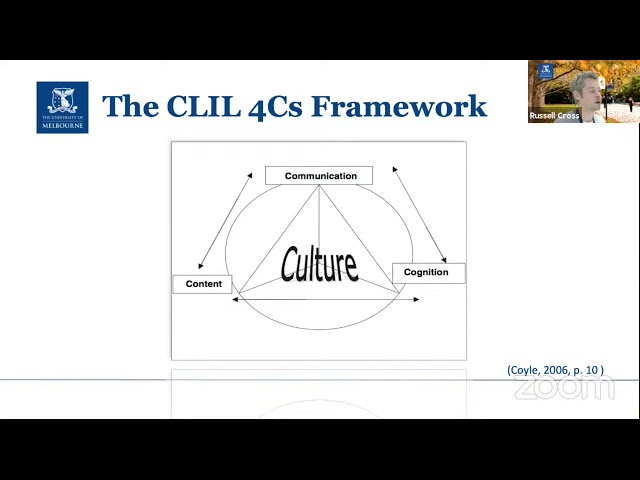

Since being identified as a key strategy in the European Commission’s Action Plan for Promoting Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity 2004-2006, the global spread of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) has proliferated rapidly in the last 10-15 years for the teaching and learning of foreign languages. In Australia, for example, Coyle’s (2007; Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010) model has been especially influential for enabling teachers of Languages to understand, identify, and plan for the learning demands that arise when language/content are brought together as simultaneous dual-teaching goals, such as learning a new scientific concept through Japanese or Italian, for non-background speakers of these languages. CLIL continues to attract strong interest for its capacity to support innovative ways to engage students and deliver high quality language programs. However, this presentation argues for the potential of CLIL beyond Languages, and what else we might learn from a dual-focused approach to languages/content for general pedagogy. In particular, I focus on its potential contributions for better understanding the relationship between language, thinking, and learning (with particular attention to dialogic teaching); understanding and positioning all learning (and learners) as ‘risk-taking’; and implications for engaging with and supporting cultural and linguistic diversity across the curriculum.

Australia is a highly diverse multilingual society that is nevertheless strongly monolingually English-speaking. It, like Anglophone countries everywhere, faces the challenge of recognizing the value of multilingualism as well as of language teaching for all students. English is so powerful globally that native English-speakers often see little or no need to learn other languages or to support the maintenance of other languages. The global domination of English as well as a strong monolingual mindset in favour of English combine together to make it easy for many Australians (as well as many other English-speakers elsewhere) to think that it is only natural that everything should happen in English (if this is not already the case) and that it should logically be experienced and understood in English. This mindset is a paradox, given Australia is extremely linguistically. Changing this mindset is one of the most pressing challenges standing in the way of successful language learning in this country. In this talk I outline specific examples of the many different issues and challenges language educators in Australia face and have to deal with – both within schools but also more broadly in society. I also give examples of the kinds of arguments that need to be made in response to support multilingualism and language education in this country. I also argue that a positive approach is more likely to change minds and attitudes.

Prenant appui sur les conclusions des différentes expérimentations scientifiques visant le renforcement de l’enseignement des langues et de la culture polynésiennes à l’école réalisées de 2005 à 2014 et ayant pour ambition la sauvegarde du patrimoine linguistique et culturel et la réussite des élèves, le ministère de l’Education du Gouvernement de la Polynésie française s’est engagé à mettre en place un enseignement bilingue français-langues polynésiennes à parité horaire dans certaines écoles. En cohérence avec la littérature scientifique en matière d’enseignement précoce des langues, cet enseignement bilingue a concerné le cycle 1 dans un premier temps. Une entrée progressive des paliers des cycles supérieurs est opérée d’année en année. Ainsi, après avoir obtenu l’accord de la communauté éducative, notamment celui des enseignants, des parents et des élus, 3 écoles se sont engagées dans ce dispositif en 2019-2020 et 7 autres l’ont intégré en 2020-2021. Afin d’assurer une couverture de l’ensemble des archipels du territoire polynésien, il est prévu d’y intégrer 7 autres écoles en 2021-2022. Au-delà des incontournables aspects juridiques et organisationnels, cette intervention abordera la question de l’enseignement de(s) et en langues polynésiennes et de l’enseignement articulé du français et des langues polynésiennes.

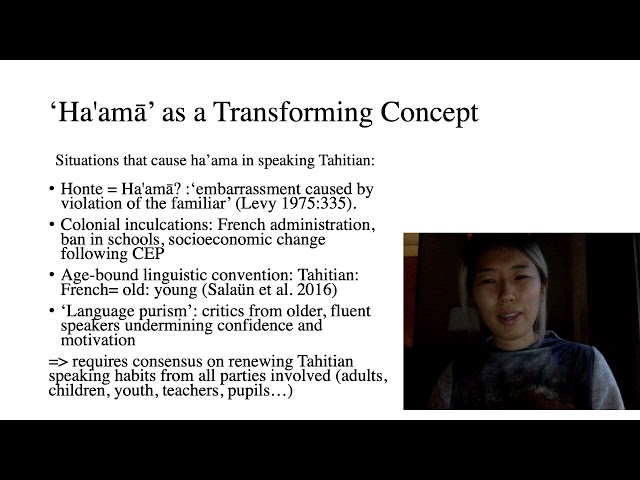

This paper aims to highlight the historical role and contemporary challenges of the Maohi Protestant Church (Église Protestante Maohi/ EPM) in revitalizing the Tahitian language. With the continuing dominance of French as the language of instruction in schools, it is evident that there has been a considerable decline in the practice of speaking Tahitian amongst younger generations. Building upon existing studies centred on public education, this research illustrates the supplementary role of EPM between households and public education by providing language education in its spiritual contexts; “the return to fenua”. This study is based on the participant observation of pedagogical and religious activities, and conversations with the younger members of the parish of Maatea, Moorea, aged 18-35. This paper first suggests “haama/ honte” as the predominant psychological factor for the reluctance in speaking the language, which is in turn caused by the absence of regularly speaking Tahitian and the resulting lack of linguistic skill as a consequence. While recognizing EPM’s historical legacy in preserving Tahitian, I also scrutinize the “sacralization” of the language. While their role contributes to cultural empowerment through the language that has been deprived in the colonial context, the use of Tahitian is limited to the religious spheres. The exclusivity of Tahitian in formal religious services and announcement could therefore ostracize the language and its speakers from younger generations, further widening the separation between religiosity and the everyday; “the official discourse in Tahitian” and “the informal conversation in French”.